How can you increase the "GDP per capita" in any country?

There are two ways:

1. Increase GDP

2. Reduce the population

At a recent strategy off-site I led, a debate arose: can a metric like payroll-to-revenue ratio be a strategic goal?

No, it can’t.

Any goal in the form of a fraction is about efficiency. But efficiency can’t be a strategic goal—with only one exception.

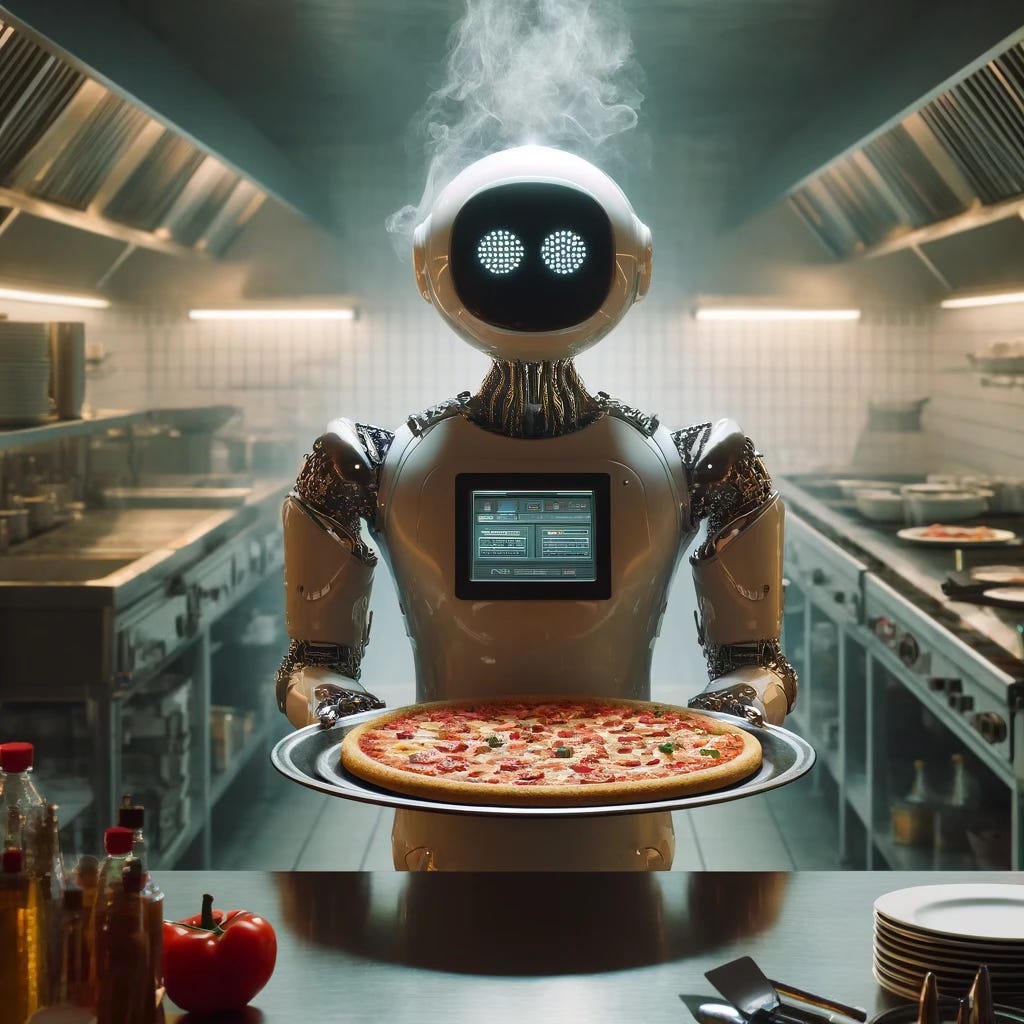

Robotic pizza

In 2013, the fast-food market looked archaic.

– Too much manual labor

– Too little automation

Alex Garden, who had worked for tech companies all his life, filed a patent for cooking food as it was being delivered. And in 2015, he co-founded Zume Pizza, a startup that received $445 million in investments but was liqudated in 2023 and became one of the biggest flops in Silicon Valley history.

Garden believed in efficiency and automation.

He built a company that made pizza with robots in a warehouse and then finished it the robotic kitchens on the wheels.

When you ordered a pizza, a bus full …