Bill Gates said, “Your most unhappy customers are your greatest source of learning." This makes sense, but using such customers as the only source of such information may bias your strategic thinking.

This may be why few MS Windows users are big fans of the operating system.

But there is a better way, simple and complex at the same time.

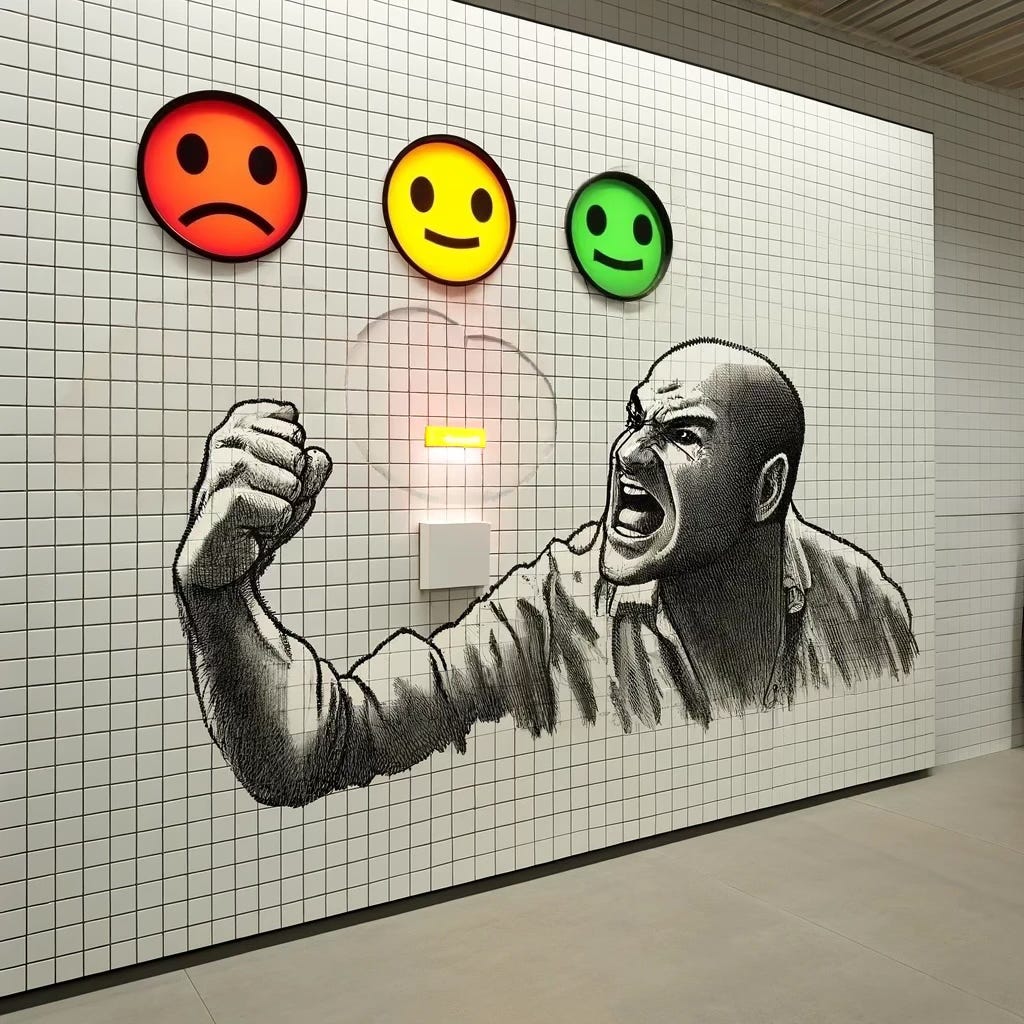

Customers seek revenge

Twenty years ago, unsatisfied customers could merely grumble and complain to their co-workers. These days, they have a powerful weapon against companies: social media.

A few months ago, the Wall Street Journal published an article stating that “the percentage of consumers who have taken action to settle a score against a company through measures such as pestering or public shaming in person or online has tripled to 9% from 3% in 2020, according to the study."

So, more unhappy customers go public and share sarcastic stories about their bad experiences online.